For women, life is a constant battle for emancipation from bonds

Reprint of the author's note from The Brass Notebook - how one Indian 'tomboy' grew into a free-spirited feminist activist, a tireless champion of women's rights.

By DEVAKI JAIN

New Delhi, September 2023

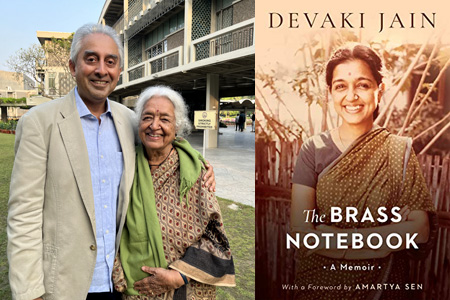

Devaki Jain (right) in New Delhi's India International Centre, attending the 2023 Chameli Devi Award (started by her family) for deserving women journalists. And a younger version on the cover of her book, 'The Brass Notebook'. Pictured here with Vijay Verghese (left) who attended the twin BG Verghese Memorial Lecture.

Publishing ‘my life’ at the age of eighty-seven makes me feel somewhat like Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ancient mariner. "I fear thee ancient mariner! I fear thy skinny hand! And thou art long, and lank, and brown, As is the ribbed sea-sand, " says the young man to a mariner he meets. I have skinny wrinkled hands, white grizzly hair and a wrinkled face.

Yes, indeed, writing this story of my life has been like coming off a ship, wrecked by a storm, or out of an ancient cave in the mountainside, as everything that I try to remember seems long ago and yet like yesterday.

A journey spanning seven decades of ‘adult’ life is certainly a long one. It was natural that there were many waves, storms and stillnesses that I witnessed over those eras and I thought my experiences may reveal some new pictures from the big picture, painted by historians. Persons who may have lived, say, seventy adult years in other periods may find my stories trivial or commonplace but that is in fact the excitement of history. That in some ways it is never new, nor ever old!

The daunting business of memoirs

It is intimidating if not impossible, to even consider writing one’s story if one belongs to the era that I belong to — that is the mid-twentieth century. The era was dramatic in many ways — but for us, born in India, it was India’s arrival as a free nation as well as a significant one, not only because of the prime-ministership of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, which left its stamp on the world, but also the ingenuity and charismatic leadership of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Devaki Jain

How was I to project what can be called ‘my story’ in a landscape which was so full of originality, so revolutionary, so full of great characters who walked and scripted the history of free India?

How to project what can be called ‘my story’ in a landscape which was so full of originality, so revolutionary, so full of great characters who walked and scripted the history of free India?

Thus the task that I have undertaken, to write my story, is not only intimidating but even seems ridiculous. Especially since I had no great role to play in this part of India’s history. I was more like an ant, while in fact there were many individuals and movements which were like the elephant or the tiger, or a storm.

To describe how one arrived at a particular point in India’s social history, where one was considered as a pioneering person in terms of the Indian women’s movement, does not seem a significant story. Hundreds of other women — and it continues even today — have made greater contributions than mine to the women’s movement as well as to India’s political history. So one again is like an ant.

Yet there was a demand that I should write ‘my story’ and the demand was backed up by a grant to encourage me to write it, and so here I am, writing it.

The desire to put into words and pages everything that happened to me and that I witnessed has been a pull for decades. At the risk of being laughed at, I would even say I wanted to write about my experiences from the time I was a teenager — I began to keep a diary at the age of twelve. Why this desire to write about what one is experiencing? Could it just be ego? Or the love of writing?

Incredible women who influenced me

The desire got a big push thanks to the extraordinary, unexpected experience of meeting novelist Doris Lessing in London in 1958. I was introduced to Lessing by another writer, Ann Piper. Lessing was at work then on the pioneering novel published as The Golden Notebook (1962).

Radical in both its form and its politics, it tells the story of a writer, Anna Wulf, who finds she is suffering from a peculiar kind of writer’s block. She can still write, but she cannot find a unified narrative that unites all the episodes in her story. Desperate to overcome this block, she buys herself four notebooks, each with a different-coloured cover. The black notebook will tell the story of her life as a writer, the red notebook her political life, the yellow notebook will have her attempts to make ‘stories out of my experiences’, and the blue notebook will serve as a kind of diary.

On reflection, I think I was born free. I did not only yearn for freedom but seized it, at every chance I got, whatever the grown-ups said: I climbed the tallest trees, went horse riding, did not spend my time merely envying my brothers their bicycles but riding them

This strange division of notebooks helps overcome the initial block, but at the end of this exercise she tries something further. She buys a fifth, golden, notebook, which she hopes will serve to unite the four notebooks. This remains a hope, but the sheer effort of working through her life and her experiences gives her a more valuable insight: a sense of what is, realistically speaking, possible.

My conversation with Lessing lasted for hours, after which she said to me, "You must write your story now. Send it to me, I can help you." I wish I had, but other things — the subject of this memoir — got in the way. Sixty years have passed since I first thought of writing my story. In this time, my self-confidence and my skills as a writer have diminished. I hope no longer for perfection, nor to write my own golden notebook. Instead, I am now thinking of another metal — pittalai, the word for brass in Tamil, the language of my childhood.

In those early decades of the twentieth century, when I was growing up, most of the cooking and the heating of water in the middle-class families of Bangalore and Madras (as Bengaluru and Chennai were then called) was done in large brass utensils, better able than steel to withstand the high temperatures of wood stoves. The interior was treated with some other metal to stop the food from being poisoned by the oxidation process. Brass is a hardier, homelier metal than gold. It represents not perfection or unity, but an honourable imperfection consistent with my own limits. It seemed more appropriate as the receptacle for my story.

On reflection, I think I was born free. I did not only yearn for freedom but seized it, at every chance I got, whatever the grown-ups said: I climbed the tallest trees, went horse riding, did not spend my time merely envying my brothers their bicycles but riding them. I did these things, disregarding the conventions that tried to dictate how girls should behave. While there was much orthodoxy in the family, there was also accommodation. The term used in those days to describe girls like me was 'tomboy'.

I am now proud to say this 'tomboy' went on to live her life as a feminist, another way of saying that I lived, to the extent that I could, as a free woman. And to be a free woman, with all its risks and costs, has meaning not just for my public life as a writer, scholar and activist, but my private life of love, friendship, marriage and family.

Looking back, I am almost convinced that freedom, or emancipation from bonds, comes from fighting for freedom, which in itself is the affirmation of freedom.

Reprinted with the author's permission from her memoir The Brass Notebook published by SPEAKING TIGER BOOKS LLP copyright © Devaki Jain 2020. The book is available on Amazon.

Devaki Jain is a prominent Indian economist and writer, known for her tireless activism promoting feminist causes. She graduated from Mysore University in 1953 and went on to St Anne's College, Oxford, to gain a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Her various books on empowering women in India brought her into the spotlight. In 2006 the Indian Government awarded Jain the Padma Bhushan, one of the country's highest civilian awards. Devaki Jain continues to write, work, and live in New Delhi and Bangalore.

Post a comment

- HOME

- BUSINESS

- DEVELOPMENT

- ENERGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- HEALTH

- INFORMATION

- POLITICS

- SECURITY

- SHIPPING

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- TRENDS

Long term impact of Gaza attack on Israel

Consequences of Palestinian conflict and finger-pointing in the blame game ... See world opinion

Curse of curation

PR-speak is turning our conversations into outright gibberish... more…